Photograms – Before Instagram, Computers, or Cameras

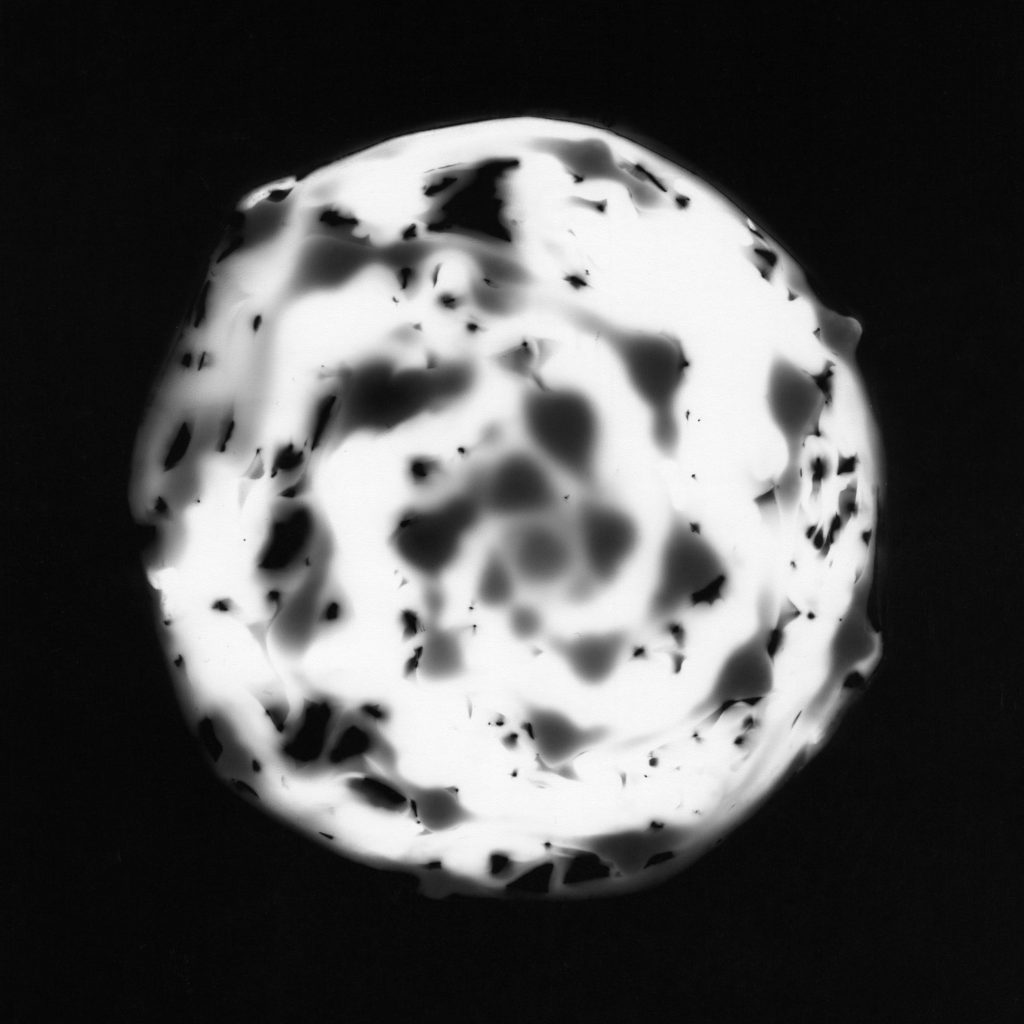

Posted on · Categories PhotographyPhotograms expose a different and fascinating dimension of everyday objects. This project reveals how the internal symmetry of fruits and vegetables recalls other natural structures, from sea life to deep space events, creating a bridge between the everyday and the unknown.

I have worked with 13 different fruits and vegetables over the past two years. For the next few months I will be creating new pieces in this series and posting them here.

The project began in 2015, during a meditative 6 minutes in the darkroom spent watching my first photogram slowly emerge from a blank sheet of paper. A galaxy of spiraling dark spots on a white disk ghosted into life against a velvety black background. It was so unlike what I had imagined would be captured, so abstract and beautiful, I couldn’t wait to try more. This mysterious image appeared from 12 seconds of light shining through a slice of everyday red cabbage, directly onto light-sensitive paper.

Photograms are a throwback process even in the vintage world of film developing. All you need is light-sensitive paper and chemical fixative. In the earliest days of photography, before cameras were accessible or portable, many artists and scientists experimented with photograms, from the scientific algae cyanotypes of Anna Atkins to the conceptual rayographs of Man Ray. As cameras rose in popularity, photograms faded into obscurity, but they are not a dead medium. Contemporary Ohio artist Anita Douthat uses dress fabric on large sheets of paper exposed by direct sunlight. In Norway, Lise Bjorne Linnert uses ash and breath to create a record of her presence.

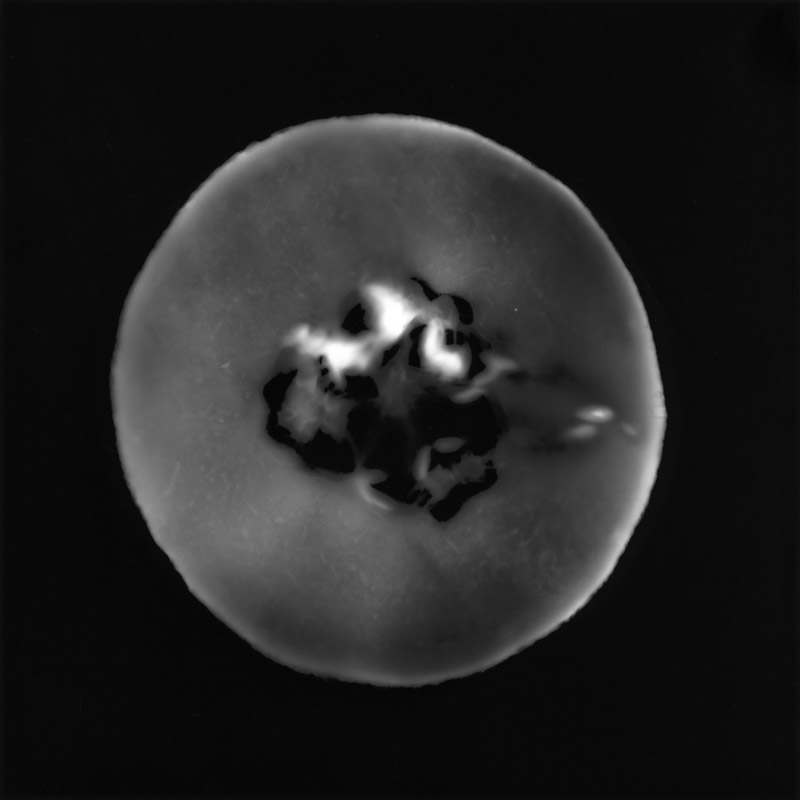

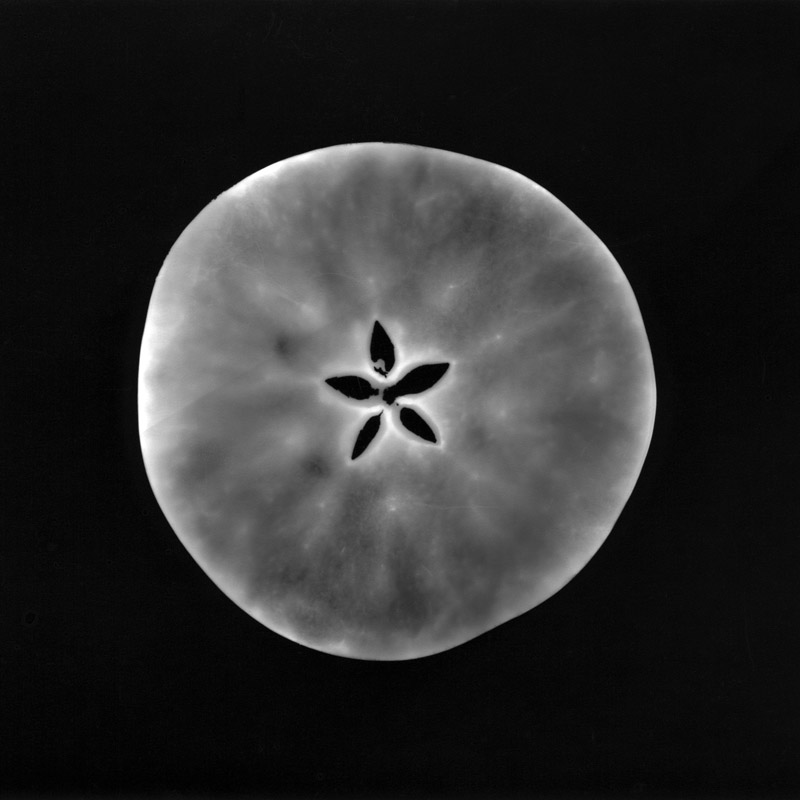

I love how the simplicity and directness of the photogram process leads to such mysterious and abstract results. Apple slices reveal an unexpected five-point symmetry, like a sand dollar, and the seedy void in the center of a cantaloupe slice is a mystery rather than a clue. At the same time, they are pure and true representations of their source.

Left: Pentamer 2, photogram, 8” x 8”, 2015. Right: Trefoil 2, photogram, 8” x 8”, 2015. © Emily Miller.

Left: Pentamer 2, photogram, 8” x 8”, 2015. Right: Trefoil 2, photogram, 8” x 8”, 2015. © Emily Miller.

Each slice of fruit is unique, changing form depending on whether it was sliced from nearer the center or the edge of the whole. By holding a slice up to the light, I can try to guess how the photogram might turn out, but I am always happily surprised by what is revealed, and what is hidden, in the final image. The image, and the process, remains an open question. That is the reason I keep going back for more.

Two years later, I tried to re-create my first photogram with a new slice of cabbage. After tweaking and testing different exposure settings for over an hour, and developing only flat white circles or indistinct blurs, I conceded that Cabbage #1 should stand on its own, speaking to the magic of a fleeting process that can never truly be reproduced.

Emily Jung Miller

Emily Jung Miller